by Mirhanda Alewine, communications coordinator

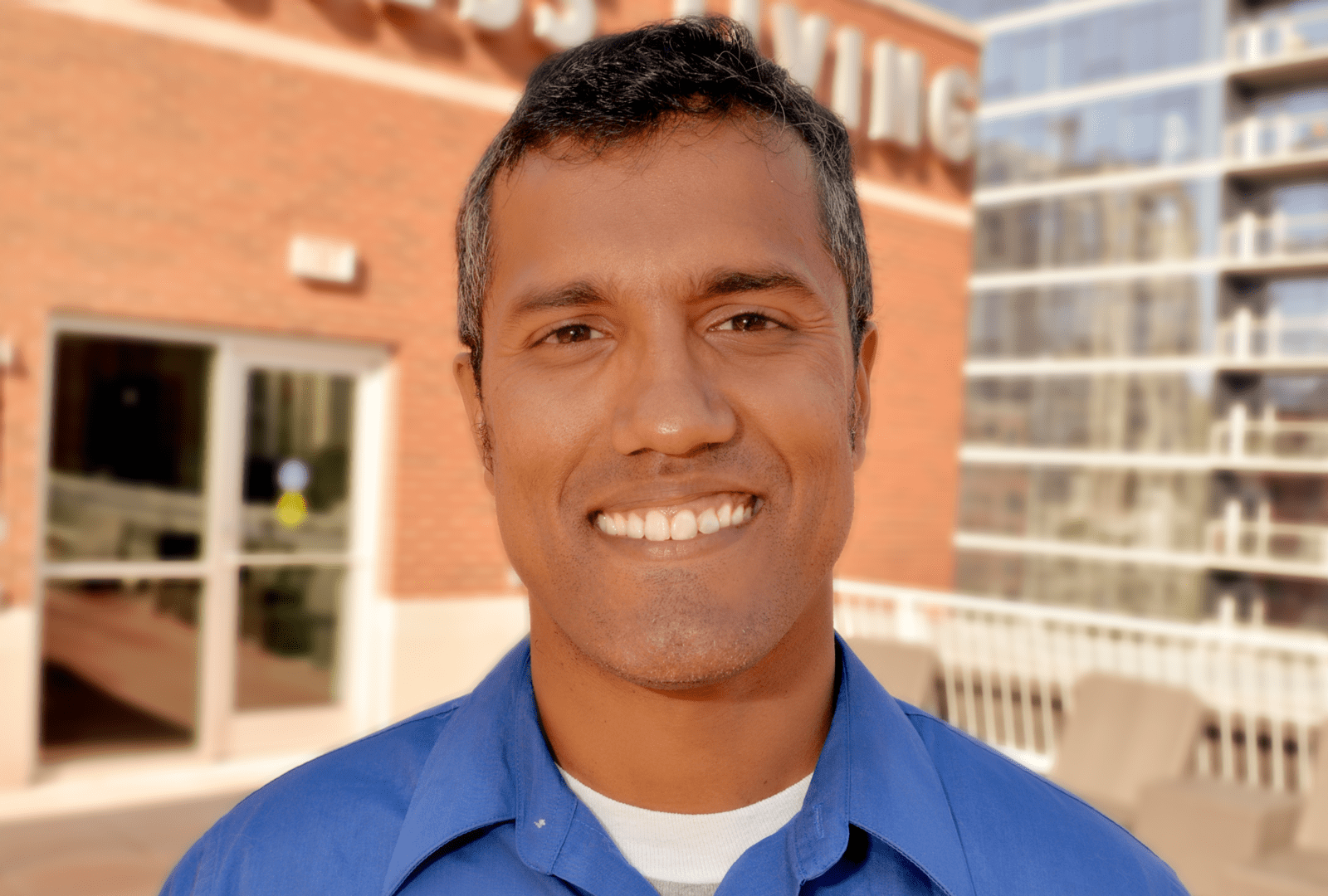

Bhuttu Mathews, a member of Illinois Alliance for Sound AIDS Policy (IL ASAP), uses his experiences as an immigrant and person living with HIV to advocate for other Illinoisans experiencing health inequity.

Take a moment to imagine that everyone has access to health care, regardless of race, sex, gender, age, socioeconomic status or level of ability. When someone is sick or hurt, they are able to go to the doctor to receive medical attention. Recommended visits to general physicians are common for preventive screenings. Health care professionals do not perpetuate racial, gender, or disease-related stigma. Health insurance providers do not discriminate based on pre-existing medical conditions. Everyone can afford necessary medications and treatments. People don’t live in fear of overwhelming medical costs due to unexpected or chronic illness. Individuals are taught about risk behaviors and prevention methods in easy-to-understand language.

Take a moment to imagine that everyone has access to health care, regardless of race, sex, gender, age, socioeconomic status or level of ability. When someone is sick or hurt, they are able to go to the doctor to receive medical attention. Recommended visits to general physicians are common for preventive screenings. Health care professionals do not perpetuate racial, gender, or disease-related stigma. Health insurance providers do not discriminate based on pre-existing medical conditions. Everyone can afford necessary medications and treatments. People don’t live in fear of overwhelming medical costs due to unexpected or chronic illness. Individuals are taught about risk behaviors and prevention methods in easy-to-understand language.

This is not the reality of 2015. Despite strides toward equitable health care, such as the Affordable Care Act, there are still populations of people who feel that going to the doctor is a luxury reserved for those living with money and without stigma.

However, health equity is possible. There are people who imagine this world daily. People who work to create this world through their work and advocacy. People like Bhuttu Mathews, who make every effort to turn this imagination into a reality.

“By and large, I had a great childhood.”

Mathews speaks in a clipped accent, emphasizing his AHs and rolling, ever so slightly, his Ls. This accent is one of the remaining intimations of Mathews’ childhood in Mumbai, one of the most densely populated cities in India.

Living with his parents and brother, Mathews had a typical, middle-class Indian childhood. His father worked as an electronics engineer while his mother was a civilian for the Indian army, and Mathews received a rigorous education in India’s school system.

Mathews concedes, however, that the conservative and religious undertones presented to him as a child ultimately harmed his sense of self.

“On the face of things, I had a really [pleasant youth] that I couldn’t complain about, but what I didn’t realize at the time was that I was developing a lot of shame and stigma about who I was.”

“The sexual coming out process was really, really hard on me.”

In 1991, when Mathews was 16, he and his brother made the trek from India to the U.S. with student visas in hand. Their parents wanted a better education for their sons (a desire that kindles so many stories of immigration), and the U.S. seemed like the obvious option.

“[Moving] was a huge culture shock. It was very jarring.”

Mathews settled in Chicago, a completely unfamiliar place, separated from his father and friends, and it was difficult for him to acclimate. Though Mathews was able to excel in his high school classes and met people “by joining the high school swimming and soccer teams,” he began to struggle.

The generally open and accepting nature of the U.S. was foreign to Mathews, who was accustomed to a hyper-traditional environment. When he started college, Mathews’ newfound “freedom to be sexually open without fear of discovery” was accompanied by a distinct and unexpected feeling of isolation, and he began a long battle with depression. “College was a very painful experience,” Mathews admits, and he felt his life spiraling out of control.

In 2004, during his last week of final exams, Mathews was diagnosed with HIV, the final blow of his tumultuous college years delivered as a parting gift. At the time of his diagnosis, he was employed and had insurance, but it only heightened the depression with which he was already dealing. “From there everything just cascaded down. As is typical when you go through that whole spiral, there was one insurance payment that was missed, and they immediately kicked me off right away.” When he attempted to get reinstated, the insurance company told him he was too much of a risk because of his positive HIV status.

“I resolved that this was going to be rock bottom.”

Mathews struggled. His HIV diagnosis was closely followed by the expiration of his student visa. Mathews seemingly had nowhere to turn. Returning to India felt impossible because of the country’s pervasive homophobia and stigma, as well as the resulting lack of quality care available for people living with HIV. However, staying in the U.S. without a visa also felt impossible, particularly without health insurance or an emotional support system.

Mathews’ partner at the time volunteered to serve as his immigration sponsor, and Mathews moved in with him. This relationship, however, soon grew emotionally and physically abusive. Mathews’ partner not only threatened to stop sponsoring him, but became violent as well, and Mathews knew he needed to escape this toxic and dangerous relationship.

With nowhere else to turn, Mathews spent the next few years in transitional housing programs, including Next Step and Bonaventure House. “It’s fortunate, at least in Illinois, Chicago especially, that we have agencies [devoted to combating the HIV epidemic], so that an immigrant living with HIV does not feel like they’re isolated.”

These transitional programs provided Mathews with the structure, resources and support systems necessary to get back on his feet. He resolved “to make sure it doesn’t get any worse than this,” and things slowly began to fall into place for Mathews. Due to dangerous attitudes surrounding HIV in India, Mathews began to receive support from AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) and was granted asylum from the Department of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

“Most people are not looking for a hand-out; they’re looking for a hand up.”

Mathews’ unique experiences and perspective taught him how difficult it can be for someone with HIV to receive vital care. Thus, an advocate was born. Mathews attended HIV Advocacy Days in Springfield, and this experience “really convinced [him] that [he] could do [this work].” In 2010, Mathews received a job offer from Access Living, an organization that connects people living with disabilities to resources, and he now helps around 2,000 people a year.

Today, in addition to his work with Access Living, Mathews takes night courses in preparation to earn his Doctor of Physical Therapy degree and spends time with his partner and dogs. This sense of normalcy once seemed impossible. Mathews now understands that health equity is only possible when everyone receives medical care in conjunction with emotional support and compassion. Because of the help that Mathews received from key Chicago support organizations, he was able to become a partner in the fight for health equity, and today he devotes his days to giving a “hand up” to others who need it.