Maxx Boykin on stigma, Laquan McDonald and the end of state and community violence

A steady fire is burning in Chicago. The flames of racial injustice have licked the edges of one of America’s largest and most powerful cities since long before the Great Chicago Fire.

Almost one month ago, that fire was fed by the release of a video — a video showing one more example of police-led brutality against people of color in the city of big shoulders. Chicagoans have taken to the streets to call for resignations, for justice, for change.

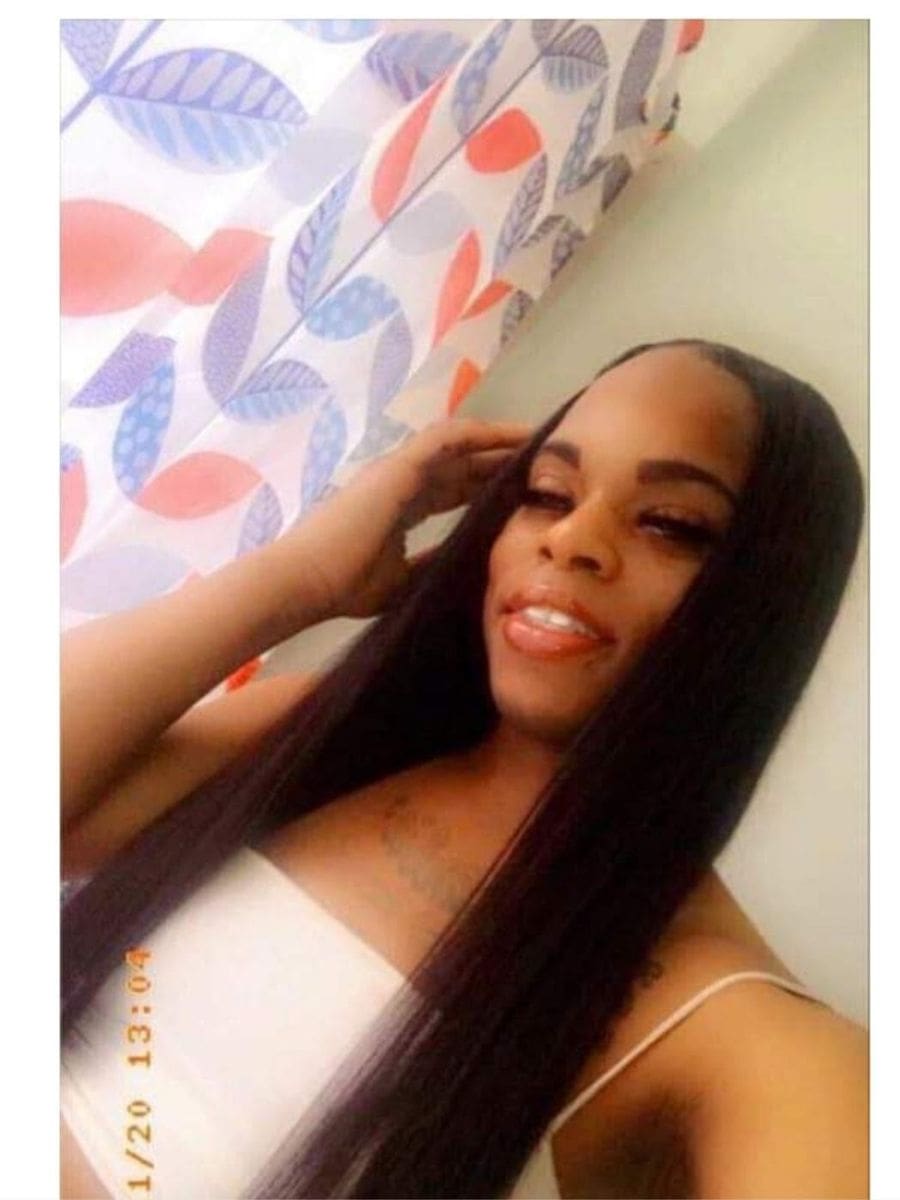

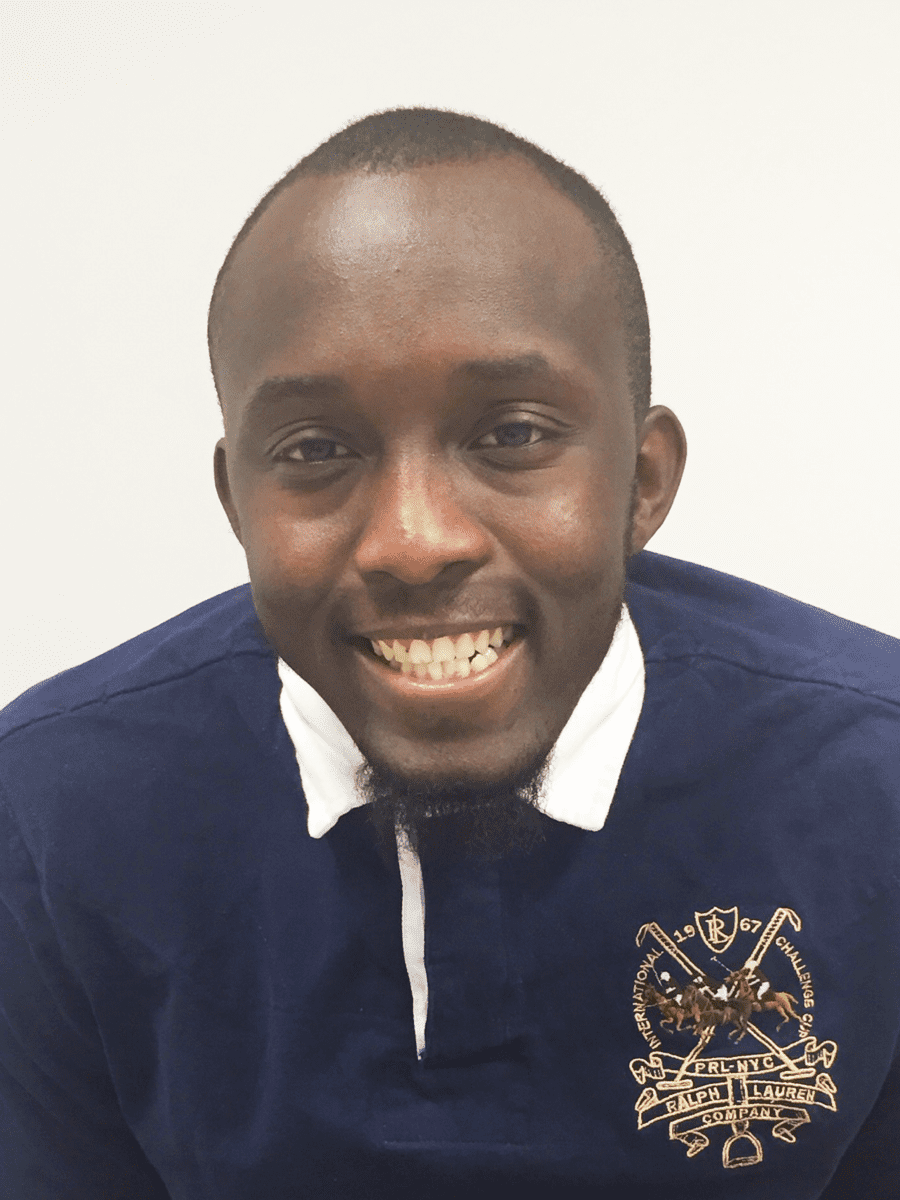

Maxx Boykin is stoking those flames of action. He serves as a community organizer with the AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC) and Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100), which mobilizes youth to create justice and freedom for all Black people. Boykin leads communities to improve access to health care, end state violence, erase HIV stigma and liberate Black lives in Chicago and across the nation.

“What we’re fighting for is black liberation,” said Boykin. “That is something that has never truly been seen in this country, but something we’ve always been fighting for.”

AFC sat down with Boykin earlier this month to discuss the apparent coverup of the murder of Laquan McDonald and how it relates to the larger intersection of the movement for Black lives and HIV.

AFC: You’re from Stockbridge, Georgia, near Atlanta. What brought you to Chicago?

Boykin: I came up during the Affordable Care Act implementation and worked with Enroll America to do outreach and education. I helped get people signed up and helped keep them signed up. We touched in my region over 400,000 people. The city of Chicago has a lot of people, and the South Side in particular [which was in Boykin’s region] has a lot of uninsured, including in my neighborhood, Washington Park.

What inspired you to get into the health insurance arena?

Health insurance was really important to me because I’ve seen how it impacted people’s lives. My aunt, who had cancer for four years, was not able to get treated — not because she didn’t know about the cancer, but because she couldn’t pay for the treatment. And to see that happen made it really important to me. I also have seen people stigmatized and die from stigma of being a Black gay or bisexual man or being a person that’s living with HIV and not get the help that’s out there. People don’t know about the treatment options out there — and that’s why I thought this work was important.

You’re also deeply engrained in Chicago’s youth empowerment movement.

Yes — I’m part of Black Youth Project 100. It’s a group of activists and organizers throughout the country who are working toward Black liberation. We operate under a Black queer feminist lens, so that the most marginalized people in our community are uplifted. We do direct action to bring awareness of the wrongdoings of those who are in power — not just awareness, but to push those people of power to not just recognize the situation but to move forward on new legislation or hear from those people who are typically silenced.

In the wake of what appears to be a high-ranking cover-up of the now-infamous video of Laquan McDonald being shot to death by a Chicago police officer, what is BYP100 doing to fight back?

We’re putting the spotlight on the fact that the city of Chicago spends 40% of budget on the Chicago Police Department. That means 40% of our taxes go toward funding the police, which is the city’s largest agency, rather than Black futures. The city has taken away mental health clinics in the city, as well as child care, our school system, after school programs and more. Those were taken away because of the failure of our state budget and the failure of our city to bulk up funding for those services, and then spend more money on programs like the police.

How does that disproportionate police funding affect Black communities?

Increased police funding can amplify state violence. State violence then perpetuates community violence. For instance, if the state takes away money from a neighborhood or fails to invest in neighborhoods that are Black and communities of color by taking away schools, etc., and then continue to over-police Black lives, they are taking value away. They’re taking away resources so people are doing things we consider illegal because they’re just trying to survive. They’re taking value away from those neighborhoods, because from the outside looking in, people don’t see value, so then from the inside looking in people don’t see value in the lives of people in their community and are just trying to do things to survive. If you’re not doing anything to keep those communities safe, you are perpetuating community violence.

When we take away people’s chance for success, then how is the state doing its job? And also in a city where Black people make up a third of the population and people of color make up two-thirds of the population, then the city as a whole is having an issue, because two-thirds of the people are not getting the resources they need.

Now that the video has been released, where do we go from here?

The police must be accountable to the people. They have not been for multiple different reasons. If you look at the death of Laquan McDonald; if you look at the death of Rekia Boyd in 2012, there is a lack of accountability and justice.

Curtailing the powers of the entity that has continually oppressed people is a start. The U.S. Department of Justice and federal government should not have to step in when these problems happen. The city and Cook County should be able to say, “We are not going to let you be a police officer when you do these things; we are not going to let you run rampant against folks, and we will shut down these systems.”

Over the last five years, Chicago Police Department officers have killed more people than any other city in the country. The police officers that have killed or done wrong in this city must be dealt with. The majority of complaints against Chicago police officers come from Black people. Only 2% of those actual complaints end up in any type of reprimand against the accused officers. Clearly, the systems in the police department have to change, and the people in charge of them need to change, because they have failed our communities on a regular basis.

One aspect of community violence is stigma, especially against people who are living with or vulnerable to HIV. How do you see stigma in the Black community around HIV and AIDS?

Stigma killed my uncle, being a Black man who wasn’t able to live a free life to be himself. As long as that is also a problem, then you also can fall into very risky behaviors because you’re not allowed to be your full self. Stigma was one of the reasons that HIV and AIDS weren’t treated earlier, and we’ve also seen that perpetuated in our own communities where people aren’t able to be themselves. What are we doing to have a support group for people who are going through these different things?

And then people aren’t getting tested for HIV; they’re like, “oh, if I’m getting tested for HIV I must be gay and doing risky things, let me not ever get tested.” That’s how we have many people who do not know their status. If we continue to stigmatize people around it, people won’t be free to deal with those things. AND if we keep criminalizing people with HIV, then people can be like, “well, I’d just rather not know [to avoid prosecution for HIV-related crimes].”

What can be done to change that?

Having more transformative and less stigmatizing sexual education is a good starting point, but also continued sex education. I think you should start sex ed very young but also continue it on through high school and college.

I was talking to one person at a conference, and he said when he came out to his mother, she said, “I don’t want you to get HIV and die.” As we know, HIV is not a death sentence, but that’s not what their parent thought. There’s been a lot of changes and new technologies since then, including highly advanced treatments to allow a person living with HIV to live a near-normal lifespan and prevent almost any chance of transmitting the virus.

Where can an organization like the AIDS Foundation of Chicago and its projects, like Pride Action Tank and HIV Prevention Justice Alliance, play a role in ending state violence?

We are embracing the fact that ending the HIV epidemic is part of greater social justice issues. Our Policy and Advocacy team is developing a health equity framework to find ways in which our work intersects. HIV and AIDS is part of a greater movement for a complete health justice. Health is a social justice issue, and HIV and AIDS as an epidemic has grown in the Black community because of those social and economic determinants of health. If you don’t have jobs or hospitals in your neighborhood, it’s hard to live a healthy lifestyle. So we’re coming together to build paths toward health justice. So we’re talking about getting people proper housing and jobs, attacking stigma, making sure that people who are trans have easier access to change their IDs, making sex safer in prisons — these are all things that can lead to better health in communities.

What can individuals do to support Black liberation?

We need to speak up when we see wrongs in communities. We need to consider how state violence affects everyone, especially young Black queer people. We must hold people’s hands to the fire when necessary and let those in power know when things aren’t right. We have to make sure that the police are accountable to civilians. We need to build communities where people can speak up when they see wrongdoing.