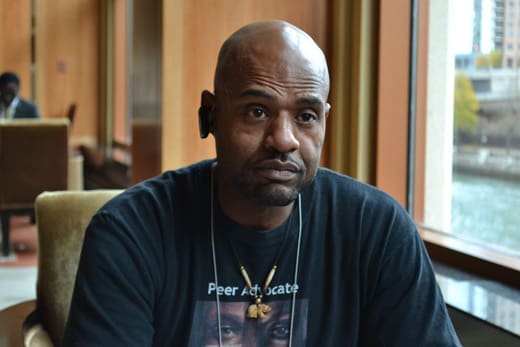

Aaron Burks, Sr., shares his story at the United States Conference on AIDS in Chicago on Saturday. AFC Photo-Ed Negron

Sixteen years ago, when Aaron Burks, Sr., robbed a Minneapolis convenience store with his fingers pointed like a gun in his pocket, he had wanted the police to shoot him down.

He was HIV-positive, struggling with stigma and his own sexual identity, and didn’t want to die from the disease.

“The process of coming to terms with being HIV-positive was very challenging,” said, Burks, 44, sitting in a Chicago hotel lobby at the United States Conference on AIDS on Saturday.

“The robbery was a cry for help.”

Instead of being killed, he was incarcerated for almost 10 years before his release in 2006. Now, Burks has a partner he loves, an undetectable viral load and a job as an in-reach coordinator for the Positive Care Center at the Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minn. His role allows him to share his hard-won knowledge with others in similar situations.

Burks’ remarkable success story would not have been possible without the extensive support he received in transitioning from prison back into society. He was part of a faith-based mentoring program while behind bars and moved into transitional housing upon release. It’s critical to have programs and policies in place to support HIV-positive offenders — in prison and as they return home, said the Rev. Doris Green, director of correctional health and community relations for the AIDS Foundation of Chicago.

“It takes time and it takes people,” Green said, to a group of 40 people at the conference. “It doesn’t matter when or how you challenge mass imprisonment as a structural driver of the AIDS epidemic — what matters is that you start, like now.”

Ultimately, the goal has to be reducing the amount of black people being imprisoned, said Laura McTighe, co-founder of the Institute for Community Justice in Philadelphia, Pa, who presented with Green.

Thirty years ago, the “war on drugs” intersected with the AIDS epidemic, she said. It was like adding fuel to a fire. Offenders released from prison still find it extremely difficult to find jobs, housing or social services because of policies implemented in the early 1980s, McTighe said. Whole communities suffer the result.

“We’re working on a scenario where our loved ones don’t have to choose between daily survival and long-term health,” said McTighe, who also serves with Green on the board of directors for the Men and Women in Prison Ministries in Chicago.

Though changing the system of mass incarceration is the long-term goal, it’s important to take steps now to improve the health of those in prison and those recently released from prison. It’s the laying of the groundwork, the building of a coalition.

Rev. Green (at left) has worked with prison populations for almost 30 years in the Chicago area.

Rev. Green (at left) has worked with prison populations for almost 30 years in the Chicago area.

With her leadership, the Harm Reduction in Prison Coalition recently fought for and won passage of a state law allowing opt-out HIV testing in Illinois state prisons.

Now, the coalition, supported by the AIDS Foundation of Chicago and other stakeholders, is pushing for condoms in the state’s prisons. It’s a small but critical piece of the groundwork for better prison and community health.

They hope to start with a pilot program in Cook County Jail.

“They say it’s illegal to have sex in prison,” Green said. “I say, ‘Are you kidding me? It’s true but you’re not stopping them.’ “

“… Having sex is as natural as breathing,” Green said. “You put a bunch of people in a cage, they’re going to find a way. We should at least make sure they’re safe.”

As for Burks, his is a daily struggle to reconcile his HIV status, his sense of self and his faith.

“I was raised in a dogmatic, religious life and everything about me was not right,” he said. “All my life, I’ve tried to make peace with that.”

But he’s doing meaningful work now helping others — and working a full-time job with benefits.

“I feel blessed,” Burks said. “I feel like God is doing it.”