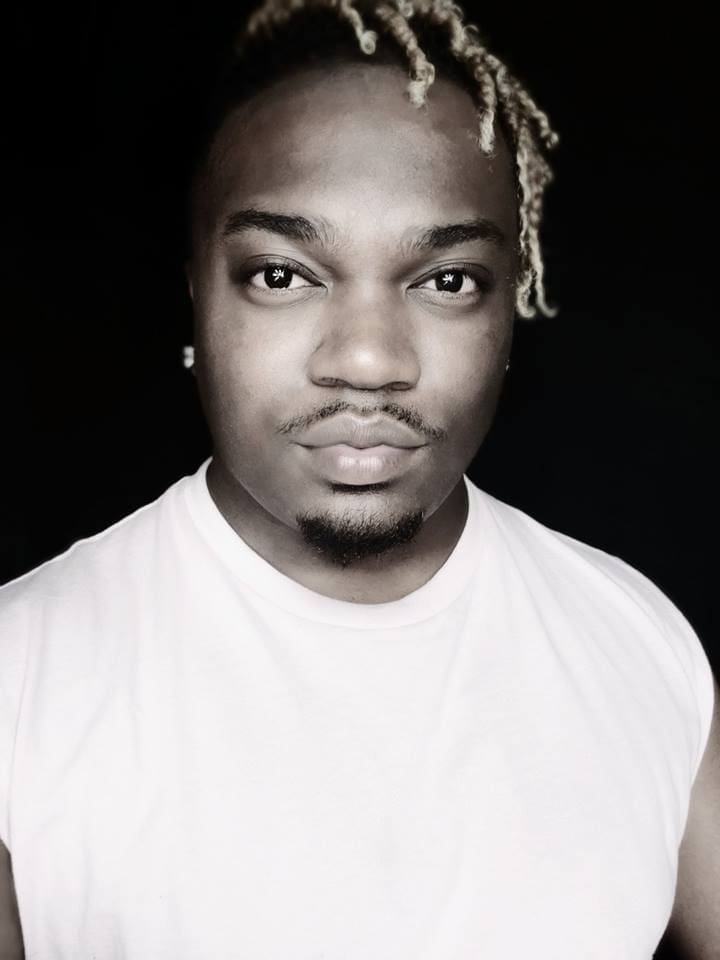

By Aaron Talley

An Ill-Fated Hookup

An Ill-Fated Hookup

In early October 2015, when Sanjay Johnson, then 22, met up with college freshman James Booth for a hookup after meeting on Jack’d, he had no idea this consensual encounter would lead to Booth accusing him of knowingly transmitting the HIV virus.

I interview Johnson over the phone. It is now three years later, and after going to court the same day of our interview, he’s discovered that his case has been pushed back until February 2019. I learn that the two had met on Jack’d in the same way hookups between gay men often do, full of silence and nondisclosure. “We didn’t know each other’s names or anything,” said Johnson. “No details, no conversation. No asking each other’s statuses. That’s it.” Johnson doesn’t speak with the nervousness I might expect of someone facing 30 years in prison; instead, the voice I hear through the phone speaks in a steady, paced cadence that befits someone born and raised in Arkansas.

The two parted ways after the initial hookup only to reconnect two years later. They became casual acquaintances, going to the movies together and hanging out. He describes the event nonchalantly. “I remembered his face,” Johnson says, “I was going through Facebook and happened to see his name. I wasn’t trying to make him a friend. It was something different. Nothing sexual. I felt, in a sense, comfortable.”

Tensions started to mount roughly two months after reconnecting. Booth disclosed his own positive status, and suddenly began questioning Johnson once again, assumedly in order to determine if Johnson was the one who transmitted the virus to him. “Things started turning down when he mentioned the situation of him being positive,” says Johnson. “[Booth] had said he was undetectable. He [asked] what he should do…and I explained to him that, you know, it couldn’t have been me who infected you…I’ve been undetectable since 2013.”

But shortly after, Johnson received multiple calls from a detective telling him that he would need to come in for questioning for “knowingly and willfully exposing someone to HIV.” Johnson was then arrested and held in jail for a week. His accuser? The same acquaintance with whom he had had a single hookup with just two years prior.

Booth claims in an article on TheBody.com that Johnson did not disclose during the initial hook-up, even when he was explicitly asked. But Johnson asserts that he would have definitely responded honestly if asked, and likely disclosed his HIV status. Since it has been so long, he can’t remember the conversation. In a later trial, Johnson was able to provide health records which corroborate that he was in fact undetectable when he hooked up with his accuser. The CDC has determined that someone who has an undetectable viral load effectively has no risk of transmitting the virus. The medical records and the science were ignored, with the judge ruling that there was still a “risk,” even though the risk is largely theoretical. This adds an unfortunate layer of irony, where a legal system meant to mediate justice between two Black gay men is ill-equipped to understand the latest science behind HIV transmission.

The accusations against Johnson now place him firmly in the snare of HIV criminalization. Arkansas is one of 34 states that have HIV-specific laws that criminalize HIV transmission. These laws disproportionately affect people of color, specifically Black people, who are more likely to be arrested and prosecuted for HIV-related crimes relative to their demographic portion of people living with the virus. In Arkansas, knowingly transmitting the virus to another person is a Class A felony, akin to attempted murder.

While the penal system might seem like an appropriate response for someone who transmits the virus with malicious intent, HIV criminalization laws are ineffective at best and racist at worst. The laws were born of outdated 1980s fear around HIV, and the legal system has failed to adjust its tenets to match the latest science. A recent study has shown that HIV criminalization laws have “no association” with HIV diagnoses, effectively illustrating that these laws do not aid in the prevention of HIV transmission. Coleman Goode, Manager of Community Organizing for the AIDS Foundation of Chicago, believes that these laws actually deter folks from getting tested. “HIV specific criminal laws are not only racist and stigmatizing but they are also an ineffective and archaic form of addressing the HIV Epidemic. Because most of the state’s laws are dependent on the accused knowing their status, many of the most marginalized are choosing to forego testing all together. We want people to know their status, share their status and arm themselves with all the information that allows consenting adults to be as sexual as they want.”

Furthermore, especially for Black gay men, these laws ignore the social determinants that lead to HIV transmission in the first place: institutional inequity and the need for intimacy in the midst of these inequities. This year alone saw a record amount of STIs, largely because of consistent budget cuts to public health for the past 15 years, and yet despite engaging in no riskier safe-sex practices than other racial cohorts, Black gay men consistently report the highest rates of HIV transmission.

The System Is What’s Guilty

These facts ultimately underscore that the system is what truly should be on trial. The state should not have the power to punish people for living with HIV when it so ardently fails to prevent transmission in the first place. Structural and socioeconomic determinants, coupled with stigma, are what result in the transmission of HIV. Draconian laws rooted in outdated fears of the 1980s cannot mitigate this fact.

More importantly, both statistics and criminalization laws fail to address less tangible determinants, such as a need for intimate connection in a world that oppresses Black gay men on multiple fronts. Scholar Marlon Bailey, in his essay “Black Gay (Raw) Sex,” argues that Black gay men wish to satisfy a craving for a “deep intimacy…a ‘being desired and wanted’ in a world where Black gay men are rarely desired and wanted.” Although ill-fated, Johnson and Booth reconnected, suggesting a need for “comfort,” as Johnson says. Intimacy cannot be litigated by a flawed justice system.

Ultimately, both Johnson and his accuser now find themselves in the nexus of a systemic apparatus that fails them on multiple fronts. But Johnson’s understanding of this system allows him to cope with his current allegations. I asked him if he is still mad at Booth, and he replies, “of course, being honest, going through the beginning stages, I became very very angry. But then I became angry at other things, like how the system does criminalize people with HIV.” Johnson is stalwart and resolute, citing conferences like HIV Is Not A Crime III (which hosted hundreds of anti-criminalization advocates in Indianapolis this past summer) as places where he finds community and support. When asked how he feels about the HIV decriminalization movement, he replies, “I’m happy it’s a movement.”

Indeed, a much-needed movement in a time where the penal system is being exposed for targeting Black men on all fronts. Johnson advises others in his predicament to tell their story. “Have the mindset to fight … grab ahold of yourself … and take control of your narrative. The narrative starts with you. You are the source, so find the strength to tell your story.”

Author Bio: Aaron is a Chicago-based writer, activist, facilitator, and educator. His work has been featured in various news outlets, including Colorlines, the Feminist Wire, The Advocate, Education Post, and Chicago South Side Weekly. An alumni of the Voices of Our Nations Arts Fellowship (VONA), he is currently working on a speculative fiction novel for young adults and teaches middle school on Chicago’s South Side. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram: @Talley_Marked and read more of his work on his blog Newer Negroes.