|

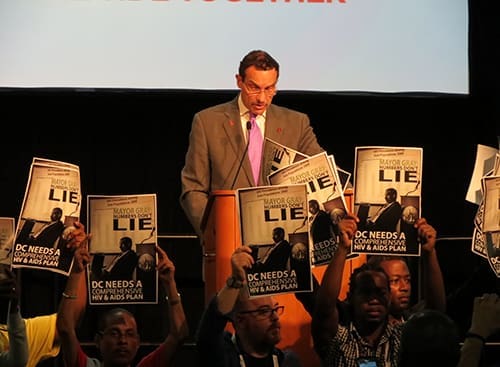

| Photo credit: Louie Ortiz-Fonseca, The gran varones |

By Bailey Williams

You might not know the name Abdul-Aliy Muhammad, but you probably know about Philadelphia’s More Color More Pride Flag: the one that expanded the colors of the original rainbow flag to include black and brown stripes with the traditional rainbow colors. Because it’s a historic Pride month underscored by the call for racial justice, the image has been circulating widely, but out of context.

The flag emerged as one response to years of activism by Black and Brown people in Philadelphia protesting a racist history, particularly in Philadelphia’s LGBTQ+ spaces. Abdul-Aliy was one of those activists, who today continues to fight anti-Blackness in all its forms, while uplifting and “loving on” Black people. You can check out their latest activism with the Black and Brown Workers Co-op here. Until then, enjoy the story of how their activism helped create change in Philadelphia.

Discovering the Gayborhood

Although Abdul-Aliy knew they were queer as early as five, they didn’t discover their hometown’s designated LGBTQ+ neighborhood–located a mere 20 minute-trolley ride away from their West Philadelphia residence–until age 17.

One day, Abdul-Aliy decided to kill some time walking around Center City. As they approached the corner of 13th and Walnut Street, Abdul-Aliy noticed a group of Black trans women and gay men hanging out. As they walked further into the neighborhood, Abdul-Aliy saw celebrations of queerness all around them. In that moment, Abdul-Aliy realized there was a place carved out for queer people. From that day forward, the Gayborhood became a big part of Abdul-Aliy’s life filled with youth events, new friendships and LGBTQ+ organizations.

“I felt affirmed (in the Gayborhood),” Abdul-Aliy recalls. “Society tells us that we don’t exist. Even in living your truth, you receive messages that your truth isn’t valid and so for me, it was affirmation that the ways I felt about the world and the ways I felt about me in the world and my intimacy was something to celebrate.”

But early on, Abdul-Aliy began to realize that this space wasn’t always tolerant of people who were also Black and Brown. Abdul-Aliy remembers racist policies and violence directed at Black and Brown people, especially trans women and people thought to be sex workers. At an early age, Abdul-Aliy was forced to contend with anti-Blackness as they celebrated their queerness.

Testing Positive and Deciding to Give Back

Some years later, Abdul-Aliy tested preliminary positive for HIV at Mazzoni Center, a health care provider focused on LGBTQ+ people. Feeling the need to give back, Abdul-Aliy started volunteering there and was eventually hired as a prevention counselor. When they were promoted, Abdul-Aliy discovered the organization’s funding models and became troubled by the response to new HIV diagnoses.

“Here I was, HIV-positive, working at an organization that said they loved and cared for our community, but they were getting incentives for us testing positive and they were excited when they linked a positive person to care because that meant more monetary gain for the organization,” Abdul-Aliy said. “I was conflicted at this point about what actually was the goal of these organizations.”

Abdul-Aliy began to lose trust in Mazzoni. Around the same time, Abdul-Aliy lost both parents, prompting them to take a step back and leave the organization.

The birth of the Black and Brown Workers Co-op

A few years later, Abdul-Aliy returned to Mazzoni and said they immediately noticed a troubling, often racist culture that included pathologizing the Black family, targeting Black staff and not valuing front-line staff.

This led Abdul-Aliy to speak with other Black and Brown workers about the need to address anti-Blackness and transphobia in LGBTQ+ organizations. Abdul-Aliy ended up supporting Shani Akilah and Dominique London co-found the Black and Brown Workers Co-op to help facilitate a critical conversation around white supremacy and transphobia within Philadelphia’s AIDS service organizations and demand change.

One of the first direct actions the Black and Brown Workers Co-op led was a disruption of an all-staff meeting at Mazzoni, following the lack of a response to the Orlando Pulse Club massacre. The Co-op disrupted the meeting and Viviana Ortiz, a Boricua trans woman, read the names of the people who were murdered.

Some months later, following sexual misconduct allegations against Mazzoni’s medical director, the Co-op organized a walk out with about 30 to 40 staff members in solidarity with front line staff and the victims of the sexual misconduct. The Co-op also released a list of demands, some of which included the firing of the medical director and CEO, who was accused of covering up the sexual assault allegations and exuding anti-Blackness.

Following this action, Abdul-Aliy left Mazzoni knowing that their activism “put a target on their back,” but continued demanding change.

Nine days later, the Co-op helped orchestrate a second staff walk out, but this time about 70 staff members walked out. The Office of LGBT Affairs and Mayor’s Commission on LGBT Affairs then released a statement of solidarity with those staff. Mazzoni Center was then required to undergo racial bias training.

Still, allegations of racism persisted, and leadership remained in place. Abdul-Aliy began to see the need to increase pressure on the organization to confront its racism.

The Med Strike

Because Mazzoni was an AIDS service organization, their former employer and medical provider, Abdul-Aliy thought the best direct action they could take would be a med strike in which they refused to take their HIV medication until the CEO and medical director resigned. Although Abdul-Aliy was unwilling to die for Mazzoni, they were willing to suffer a bit since nothing else prompted organizational change.

“As a poz person, I’m often told, ‘take your medication,’” Abdul-Aliy said. “For me, it was a show of autonomy. It was to show I could be political and HIV+ and that I could make suspending my medication a direct action.”

Their med strike prompted a lot of conversation on social media, which led to more people placing calls to Mazzoni calling for the resignation of the medical director and CEO. Within four days of their med strike, both resigned.

The Cost and Rewards of Activism

Behind the scenes, Abdul-Aliy faced a lot of criticism for suspending their medication from friends and family alike, even though they knew that they could survive a short period of time without it.

“My family was in an uproar,” Abdul-Aliy remembers. “My sister threatened to find me and shove medication down my throat…It brought up for me how someone who’s out about their status becomes this conversation that’s often about what they’re doing with their body instead of how can we support this poz person (to) live and thrive.”

Despite people’s pushback, Abdul-Aliy’s med strike was ultimately a successful tactic that they survived. It was also a catalyst and reinforcement to several calls and actions happening at the same time in Philadelphia, as activists, journalists, groups and allies called upon the city to contend with racism in all LGBTQ+ spaces.

Philadelphia’s More Colors More Pride Flag

One of the many results was the city’s development and release of the More Colors More Pride Flag in June of 2017. Abdul-Aliy was there the day it was released — not because they supported the symbol or the politicians celebrating it, but because the Co-op believed if they didn’t show up, the activists whose work contributed to this city-wide reckoning with racism would be erased from history.

“To me (the flag) is a crumb,” Abdul-Aliy said. “It doesn’t change my material conditions. It doesn’t make me less targeted in the workplace. It doesn’t make me feel safer in the Gayborhood. It’s a symbol. For other people, it was like the end of action. We did it. We have arrived. No more racism exists, which we know is a lie.”

Abdul-Aliy said the flag became a symbol people used to suggest a false arrival at equality rather than a mile marker on the long journey to Black and Brown liberation. Even today, some utilize the flag to symbolize an achieved inclusion rather than calling attention to the ongoing need in LGBTQ+ spaces to make space for and support those who are also Black and Brown.

“The truth is the rainbow has never been enough for Black and Brown people,” Abdul-Aliy said. “The rainbow was never really our symbol. The Black and Brown stripes was a way to say no. From my vantage point, it was a critique on the rainbow flag. This is a visual critique on the problem (of white supremacy and racism in LGBTQ spaces).”

After the flag was debuted, Abdul-Aliy and comrades in the Co-op continued the work of advocating for Black and Brown people, especially trans women, in Philadelphia’s LGBTQ+ spaces. A few of their subsequent wins included the unionization of Mazzoni a few months later and the hiring of a Black trans woman as the Director of LGBT Affairs in 2020.

“The biggest thing for me that came out of it is we’re here,” Abdul-Aliy said. “We’re here as ‘radical’ Black LGBTQ folks. We’ve been here. We’ll continue to press upon these systems and get our demands met by any means necessary. That’s what grounds me, but there’s so much work to do.”

Abdul-Aliy said the Co-op will remain actively engaged in the fight for Black liberation, as it’s always done.

To support and engage with the latest work of the Black and Brown Workers Co-op, follow them on Instagram and Facebook. To learn more about the history of the More Colors More Pride Flag, check out this timeline of events.