Salud y Orgullo Mexicano project manager Gilberto Soberanis describes his physical and emotional journey across borders and boundaries, both literal and figurative. Edited by Mirhanda Alewine.

Hear Beto tell his story in his own words (en español). |

In 1995, when I was 10, my mom, 2 year-old sister and I got on a one-way-flight from Acapulco, Guerrero to Nogales, Sonora. The next day, we met other families, mostly older women holding their young children, and we made our way on foot to the frontera of Nogales. There, we met the coyote, a human smuggler, who gave us instructions on how to jump and climb a wall of steel, wire and concrete standing about 30 feet high.

Somehow, it happened safely, and we continued by foot in the desert until we were greeted by another coyote who took us to a safe house. There, we waited until my father, who migrated a year earlier, was able to pay the coyote tens of thousands of dollars. Upon payment, we were released from the safe house and placed on a plane to meet our family in Chicago.

As a 10-year-old, how was I supposed to know what was going on? What was good or what was bad? I remember being mad at my parents because I was leaving my friends and school. San Luis San Pedro, Guerrero, is a beautiful small town; I remember running free, eating delicious mangoes, enjoying warm winters, spending my free time at the nearby river and taking trips to the beaches. I remember leaving a childhood where I knew who I was and where nature was my friend.

But I was 10—was all of that really the case? As an adult, I understand the struggle that my parents had to undergo, the sleepless nights where they were thinking of our future, the back breaking labor my dad did on a daily basis to put food on the table and how my mom washed other people’s clothes to bring some extra cash to pay for our school supplies.

But I was 10—was all of that really the case? As an adult, I understand the struggle that my parents had to undergo, the sleepless nights where they were thinking of our future, the back breaking labor my dad did on a daily basis to put food on the table and how my mom washed other people’s clothes to bring some extra cash to pay for our school supplies.

As a child, I was blinded by the truth. The reality was that we were living in poverty, in a place full of crime and drug cartels, a place that had little access to clean water, and going to a school that didn’t have access to electricity. Many may think that crossing the border is a big risk not worth taking and that thousands of people have died attempting get the American Dream. But what would you do if you were one of those 11 million people that were escaping crime? Drug wars? Poverty? I will forever be grateful for my parents’ decision for taking a leap of faith and for taking that journey up north.

The first five years of living in Chicago were HARD, as in, the worst years of my life to this point. I was forced to integrate into a culture I had nothing in common with; I didn’t speak English, I didn’t know what my peers were watching on TV, I had no friends and I didn’t know how to initiate conversations, since I didn’t even know what to talk about.

As a result, I started eating a lot—lots of sugar, lots of cereal, lots of burgers, lots of everything! My daily routine for the next years was to go to school, sit in the back of the classroom and not say anything, come back home, eat, and watch a lot of TV. As a consequence, I gained a lot of weight. I mean, I was a big chubby Mexican kid who didn’t speak a word of English and had no friends. I was hiding my pain and loneliness. I was living in this magical world America where everything was provided, but I was miserable and depressed. But, as an early teen, I wonder why I didn’t speak with my parents about any of this? Honestly, I don’t think I still know: maybe I was convinced that what I was going through was only temporary or that everyone was going through the same thing as me? The reality was, my parents were busy working 40-60 hours a week and that they were saving all of their money to pay the migration debt.

I managed to focus on school and learning English to avoid the reality around me. Migrating to the U.S. had a big cultural impact on me. I felt lost for years, and I lost a sense of who I was as a teen. Still feeling lost, I started looking for a community where I would feel accepted and welcomed. In high school, this meant joining sport groups, science clubs and the Heartland Alliance AIDS Ride Team to try to see where I could fit in.

As I started to find groups to fit in, I found myself more disconnected from my family. I wasn’t talking with them much about who I was and or about new interests. The reality was that I didn’t know how to tell them that I was gay. I had finally found a community in school where I could build friendships, but I had no idea who I could talk to about being gay. Latino families are not the best to talk to about sex or homosexuality in their households, because it’s that classic “taboo subject.”

As I started to find groups to fit in, I found myself more disconnected from my family. I wasn’t talking with them much about who I was and or about new interests. The reality was that I didn’t know how to tell them that I was gay. I had finally found a community in school where I could build friendships, but I had no idea who I could talk to about being gay. Latino families are not the best to talk to about sex or homosexuality in their households, because it’s that classic “taboo subject.”

As an alternative, I tried going to a youth drop-in to maybe meet people my age, but that was a disaster. On my first day a staff member violated my physical space, and I never went back. I knew I was gay and continued searching for places where I could learn more about myself and my sexuality, and I got more involved with the Heartland Alliance AIDS team. There I was finally getting the resources I was seeking.

Sadly, this wasn’t the only way I was searching for myself, though. I found a place where I could be myself without anyone knowing about it: the internet. I started chatting with people online, random people around the Chicago area, who agreed and acknowledged everything that I was going through. At that point, I knew that I wasn’t the only person in the closet and that there were many more like me around the world. After searching for acceptance, I finally found it, but it was provided to me by strangers, people I had no connection with. I decided to meet with the people I was talking to online and eventually, I became sexuality active with them. This did not last long, because, after a while, I felt used and disgusted. I had found a piece of me that I wanted to protect: my identity as a young Mexican gay man.

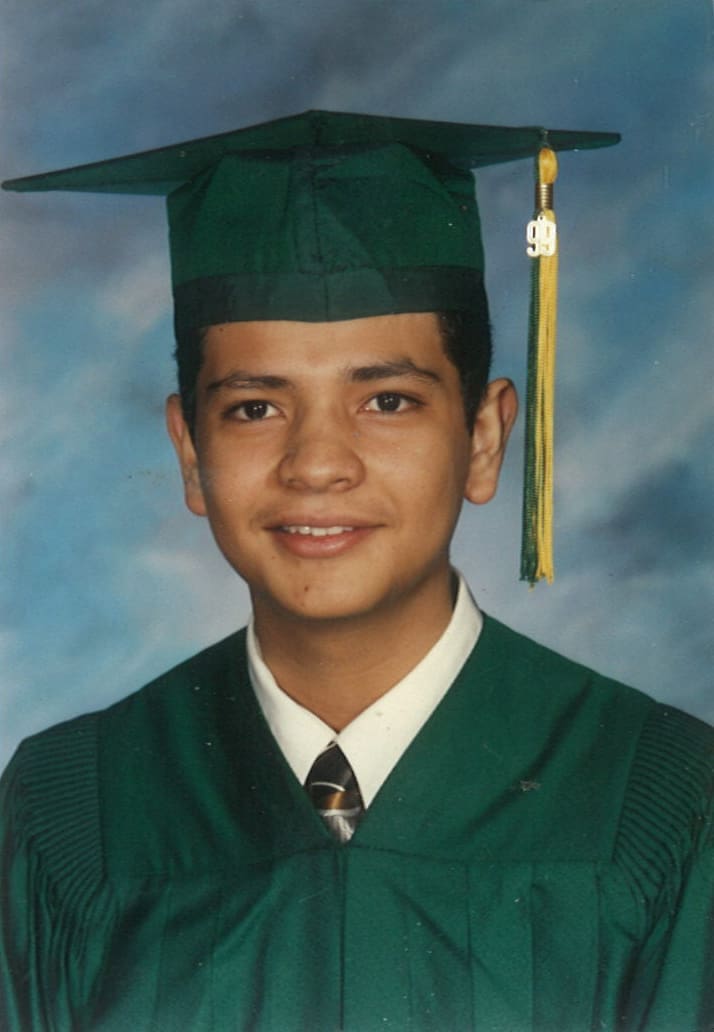

Two weeks before my prom in high school, I came down with a big flu. I remember telling my prom date that I might not be able to go to prom because I was so sick. Eventually, I managed to gather some strength and we went to prom, followed by graduation and end of school celebrations. At that point, I was dating a great guy my age, I was his prom date and we were having a blast. But, we both decided to go in for testing, because we were concerned about a potential STI symptom.

Two weeks before my prom in high school, I came down with a big flu. I remember telling my prom date that I might not be able to go to prom because I was so sick. Eventually, I managed to gather some strength and we went to prom, followed by graduation and end of school celebrations. At that point, I was dating a great guy my age, I was his prom date and we were having a blast. But, we both decided to go in for testing, because we were concerned about a potential STI symptom.

Our STI tests came back negative, but we were told to come back two weeks later to get the HIV test results. Three weeks passed, and I went in for my test results. I got sat down in a room by myself, and I knew something was not quite right because a staff member came in with a folder. My hands were cold, my heart was beating fast and my eyes were staring at the folder. They sat down next to me, and with a calm voice informed me that my test had come back positive.

Silence. There were no words coming out of me. No reaction. Just as if my life flashed before my eyes. I cried. I cried a lot. I was so scared, I didn’t know what to do. What to feel. Who to tell. Luckily, that staff member was there to provide me with support and a much-needed hug. I still remember that hug: their arms tight around my young body, telling me that things were going to be okay.

As an 18-year-old, I was lost. Confused. Scared. Angry. There are actually no words that could describe how I was feeling at that point. I had no hope that I could deal with this by myself, and I decided to tell one of my sisters, who came and met me that night. When I first saw her, I lost it; I was crying like a child who wanted to be comforted, and she hugged me. Once I had the strength to look at her in the eye, I told her that I tested positive for HIV. Silence. And that I was gay. Silence. It’s okay, she said, and gave me a hug. Never before had I felt so free — for once in my life I got the acceptance I had been searching for for years. I was able to use that strength of motivation, and I managed to put myself together.

I did it. I had finally told someone close to me that I was gay, told them my identity.

I was so scared of going to my first doctor’s appointment and starting treatment. The night before, I was at home researching HIV online. One statistic that I remember the most was that HIV-positive individuals only live for 10 years after diagnosis. I was 18 at that time, and I just got told that I was not going to live past 30. How would you act today if you were informed that you only have 10 years to live?

It took a long time to get out of that stage, but soon my case manager began to provide me with the accurate information. They explained the treatment guidelines and helped me deal with my concerns. I’m not saying that my circumstances were the hardest or most unique or that I couldn’t find someone that understood where I was coming from, but it was hard to connect with a case manager who hasn’t gone through similar circumstances.

It took a long time to get out of that stage, but soon my case manager began to provide me with the accurate information. They explained the treatment guidelines and helped me deal with my concerns. I’m not saying that my circumstances were the hardest or most unique or that I couldn’t find someone that understood where I was coming from, but it was hard to connect with a case manager who hasn’t gone through similar circumstances.

That’s when they referred me to a peer-to-peer support group. In the support group that I was attending, I was able to learn about what HIV actually is and how it was affecting me by living with it. Little by little I started learning about what the virus was, the functions and social stress that comes with being HIV-positive. For the first couple of weeks or even months, I didn’t really participate in the support groups. I just sat and listened to others’ experiences and started noticing how similar they all were to mine. Slowly, I started opening up, started sharing my story and saw how many people were nodding yes with agreement to everything I was saying. I was no longer alone; I had found a community.

I wanted to give other newly diagnosed youth the same resources that were provided to me, and I eventually became a peer educator for the support group that gave me the fire to move forward. People found my experience useful and connected with me to engage in their medical care. I was grateful for this, and it empowered me to get more involved in the community.

After a few years of sharing my story with people, I started to change the way I was dealing with my own status. I don’t know exactly when it happened, but suddenly I stopped thinking of HIV and started living. Now I live positively. I’m not going to lie, it was hard, really hard, at first. Disclosing my status was even harder. My family still doesn’t know my status, and figuring out when to tell them has always been hard to determine. I know that they will accept me for who I am, but it’s still hard. Maybe after writing this, it will help me come out of the closet again.

As a 31-year-old, I have reminded myself of all of my identities while writing this. I am Mexican. I am gay. I am Latino. I am part of a community. I am HIV-positive. I am undocumented. I’m in a supportive sero-discordant relationship. It’s really hard to come out of the shadows and face the world. Trust me, I have also been pulled over by the police and asked for a license, gotten nervous when asked to write down my social security number, waited until the very last minute to see a doctor because I had no health insurance and stayed at one job for multiple years because of the fear of not being able to find employment again due to my legal status. It’s scary to jeopardize everything you and your family have worked for, but we need to take care of our health too. Esta es mi historia, and I hope that my story reminds you that you are not alone, that I’m part of your community too. I’m just one of those 11 million people living under the shadows, and I’m privileged to say that I was granted Deferred Action for Early Childhood Arrival a few years ago. I’m coming out of the closet as an undocumented person and I hope that my story reminds you que no estas solo. Stay strong, and be proud of who you are.

As a 31-year-old, I have reminded myself of all of my identities while writing this. I am Mexican. I am gay. I am Latino. I am part of a community. I am HIV-positive. I am undocumented. I’m in a supportive sero-discordant relationship. It’s really hard to come out of the shadows and face the world. Trust me, I have also been pulled over by the police and asked for a license, gotten nervous when asked to write down my social security number, waited until the very last minute to see a doctor because I had no health insurance and stayed at one job for multiple years because of the fear of not being able to find employment again due to my legal status. It’s scary to jeopardize everything you and your family have worked for, but we need to take care of our health too. Esta es mi historia, and I hope that my story reminds you that you are not alone, that I’m part of your community too. I’m just one of those 11 million people living under the shadows, and I’m privileged to say that I was granted Deferred Action for Early Childhood Arrival a few years ago. I’m coming out of the closet as an undocumented person and I hope that my story reminds you que no estas solo. Stay strong, and be proud of who you are.