By Clair Daney

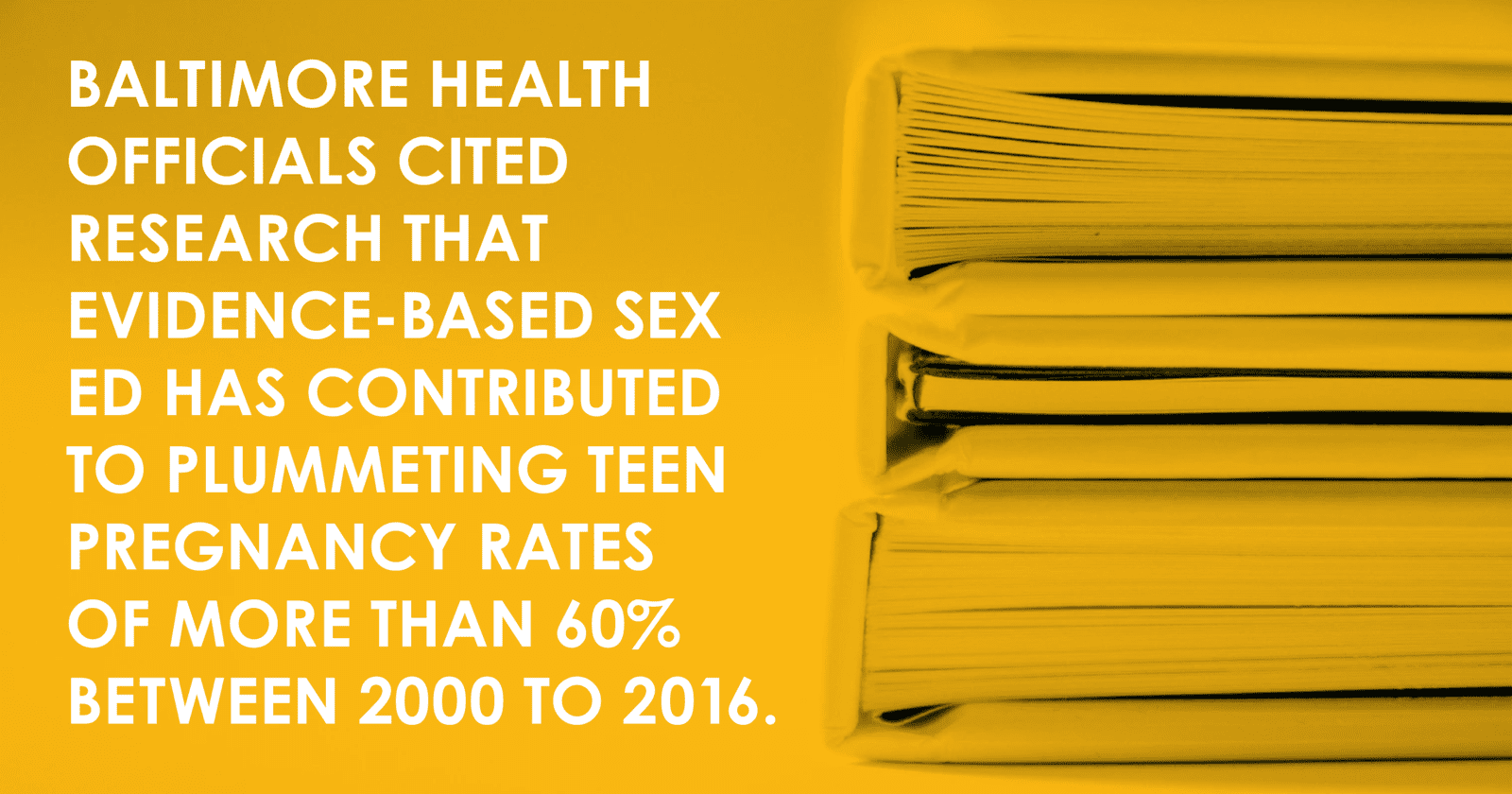

This spring, Baltimore made headlines as a federal judge ordered the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to restore $5 million in grant funding it had withheld without explanation from two local evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs.

This spring, Baltimore made headlines as a federal judge ordered the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to restore $5 million in grant funding it had withheld without explanation from two local evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs.

This story has been a single outgrowth amid the Trump administration’s broader push to eliminate science-based, comprehensive sex education in favor of abstinence-only education – an ideological approach to reducing high-risk adolescent sexual behavior that has been proven ineffective and is considered ethically problematic.

The April ruling has been called a victory for the youth of Baltimore, and for the rightful place of science and evidence in health education. In their fight, Baltimore health officials cited research that such programs have contributed to plummeting teen pregnancy rates of more than 60% between 2000 to 2016 – one major triumph in a city plagued by its reputation for health inequity and systemic disparities.

By reinstating funding for these influential programs, the ruling has restored sex ed for about 20,000 students throughout the city. But the war for science-based education rages on, with the Trump administration’s larger shift in policy threatening loss for sex ed programs across the nation.

Sex ed in the Clinton era: a story

Like politics, the pendulum of prevailing thought about the rightful teaching of sex ed has been known to swing back and forth. My own upbringing tells the story of a 90s-era education on sexual health that was cobbled together from a variety of sources.

After spending my early childhood in the Washington, D.C. area, my family moved to a small community about 15 miles outside of Baltimore in 1991. Our new town had a population of under 2,000, a Renaissance Festival and a creepy abandoned state psychiatric facility, but not much else. The student body of the middle school I attended was fairly diverse in terms of race/ethnicity and other socioeconomic characteristics, drawing together a spectrum of kids and families.

My own piecemeal experience with sex ed started much earlier than middle school. My mom read me a book about how babies were made. I learned some of the finer points of the female reproductive cycle from another girl on the playground.

Then when I was in 6th grade and most of us were about 12 years old, the county school system decided we were ready to learn about sex in school. A letter was sent home to parents, and we launched into a sex ed curriculum that formed a two-week excursion from basic science.

I don’t remember much, but I know we learned anatomy; the framework was strictly heteronormative. We sat through the requisite 90s reproductive health videos – for girls, an embarrassing encounter in the school hallway as a towering pack of maxi pads came spilling to the floor. For boys, a humiliating confrontation with a teen’s mother as he tried to surreptitiously stuff his sheets in the wash. We all had a laugh. We took a test. The topic of sex was not resurrected in school again – at least, not in an educational context.

From the age of 15 on, I was lucky to catch a nationally-syndicated radio program called LoveLine that aired on late-night radio. I tuned in faithfully night after night all throughout my high school years. Though my other experiences had provided a foundation for learning, most of the important messages I received about the complexities of sex, disease prevention, dating, gender dynamics and healthy relationships that would serve me in my adult years were carried on the radio waves.

Looking back, I’m struck by the perfunctory, patched-together nature of my education in sexual health. If topics related to sex weren’t comprehensively addressed in school, didn’t it mean they were less important than learning the Pythagorean Theorem, or how to play team handball? That these issues wouldn’t really affect us?

One memory that stays with me is about a friend in those middle school days – we’ll call her Laura. I had been over to Laura’s house to play, and I knew that her family was strictly Baptist. When the letter of consent was sent home for our parents to okay student participation in sex ed, her parents wouldn’t sign. Opted out of the daily lesson, Laura went to sit in the library by herself.

At that age, I didn’t consider the lingering impact of a vacuum of sexual knowledge might cause in a person’s life – but I do now.

What could be wrong with an abstinence-only approach?

Fast forward to 2018. If they didn’t before, now parents, educators and policymakers have a vast reservoir of research practically screaming the efficacy of comprehensive, inclusive, science-based sex ed approaches in preventing the spread of HIV and STIs, unwanted pregnancy, sexual violence and other ills.

Regrettably, in this era of Trump, decision-makers in health and education policy are resurrecting irrational fears that comprehensive sex ed somehow encourages high-risk sexual behaviors. But how could this concept be harming young people emotionally and physically?

I looked at the American Psychological Association (APA)’s official stance on sex education. The APA strongly supports empirically-based programs; especially those that clearly define dysfunctional behaviors, such as having unprotected sex or too many sexual partners, that are targeted for change; address a range of sexual behaviors; are available to all teens (including LGBTQ+ youth and school dropouts); and focus on maximizing a range of positive, lasting health outcomes.i

In direct contrast to the type of programs the APA recommends, abstinence-only programs, or the newly-euphemized “sexual risk avoidance education (SRAE)” programs currently gaining traction, typically emphasize and prioritize the message that heterosexual marriage is the only appropriate context to have sex.

The SRAE rebrand ignores rigorous studies on federally funded abstinence-only programs that show they actually have “no overall impact on teen sexual activity.”ii

Around the time the Baltimore case was being settled, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced it would lower its standard of evidence for sex ed to encourage SRAE programs being taught in the U.S.; then President Trump’s 2019 budget allocated an increased $75 million for abstinence-only education.

By definition, SRAE programs cannot distribute contraception or demonstrate how it’s used – a dangerous proposition when you consider that more than 21% of new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. in 2016 were among youth aged 13-24iii or that about half of new STI infections every year are acquired by young people under the age of 24iv. Most people who acquire HIV during adolescence are infected through sex.

Let’s also consider the recent attention the #MeToo movement has brought to the astoundingly commonplace experiences of sexual harassment and assault – experiences that in some cases are driven by ignorance of what constitutes consent and healthy sexual relationships. Don’t forget the harmful gender-based stereotypes and overt discrimination of LGBTQ+ youth that the abstinence-until-marriage philosophy fuels. Sadly, it is LGBTQ+ youth who must carry the heaviest burden of new HIV infections.

Opponents of evidence-based sex ed complain that comprehensive programs give kids too much information and, in turn, normalize sex. But normalizing sex is, in essence, a good thing – it is only specific, unhealthy behaviors and attitudes that should be checked.

On the one hand, behaviors that can make people more susceptible to HIV are well-defined and can be controlled through the tools we have readily at our disposal: up-to-date information, education, scientific evidence, contraception and other technological advances like PrEP. High-risk sexual behaviors include concrete actions that, if left unaddressed, can lead to serious consequences such as sexual violence, STIs, HIV/AIDS and unintended pregnancy. Empowering young people through skill-building around sexual communication, decision-making and assertiveness will go a long way towards curbing these behaviors.

On the other hand, sex is a broad, personal and complex universal human drive involving biological, erotic, physical, emotional, social and even spiritual feelings that typically emerge in puberty and then continue as a critical element of a person’s identity and behavior across the lifespan.

Isn’t to deny a young person basic information in recognition of human sexuality, in all its diversity and normalness, a way of cheating them out of an essential facet of their psychological and physical health and wellbeing?

Addressing the full spectrum

If sex ed programs can be said to exist on a continuum, with SRAE on one end and comprehensive, evidence-based programs on the other, I think many of us would identify our own education as having fallen somewhere in the middle, even in times of more enlightened federal policy.

I talked to Meghan Williams, a Prevention Specialist at AFC and a young leader and advocate for Chicago’s transgender community. As a former program manager for Project Elevate, an innovative, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded project to increase awareness and equitable access to HIV and STI testing and treatment for young cis- and transgender women of color, she knows a thing or two about giving young people the tools they need to stay healthy.

Meghan’s own experience with sex ed in Chicago Public Schools (CPS) sounded familiar. Her class was first given sex ed instruction from a science teacher in 8th grade — a point at which many kids had already engaged in sex. The curriculum focused narrowly on anatomy and reproductive education as relegated to a chapter in the standard biology textbook.

As with my experience, for Meghan, STIs were not part of the learning. When I asked her why she thought this might be, Meghan reflected, “I think they’re afraid the more they expose and educate the kids on sex, the more they’ll want to do it.”

Another glaring deficit in Meghan’s experience with sex ed was the lack of exploration in gender inclusion and other aspects of human sexuality. In this aspect, the education system has failed LGBTQ+ students for too long. Meghan’s experience in public schools ended like too many trans- and gender-nonconforming people before her. Bullied for being transgender, she didn’t feel welcomed by other students or even the so-called responsible adults at her school who should have been ensuring all kids felt safe. Without support, she dropped out.

In essence, Meghan was cheated out of her education as a right that every young person is entitled to. This encompassed her school experience far beyond sex ed, but what dedicated time and space could be more ideal to open a thoughtful and inclusive dialogue about human circles of sexuality, encouraging tolerance and respect for individual differences?

Meghan went on to use her painful experiences as a springboard to help other kids in the educational system: Through her work with Project Elevate, she and other AFC staffers worked with CPS and other leading organizations to assist in developing new district guidelines to support transgender students, employees and adults, including equitable opportunities to participate in sexual health education and disclose their gender identity as they wish in a safe environment.

Out of initial planning sessions, CPS has begun to implement changes. A video featuring Meghan’s story is now being shown in mandatory gender diversity trainings for school counselors and as requested by other teachers and staff. The group informing CPS’ policy is working towards additional guidelines that would require all school staff, even principals, to participate in training. Meghan and her colleagues continue to recommend a more complete sex ed curriculum that directly addresses gender inclusion and HIV/AIDS/STI prevention – not just reproductive sex.

Faculty from elementary to high schools who have already seen Meghan’s video and participated in the gender inclusiveness training have responded enthusiastically – recognizing the experience has prepared them to address gender dynamics in a more productive and responsible manner.

Striving for a more enlightened approach

For people living with and working on the front lines of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the shame our culture seems to breed around discussing sex on even the most basic level is an insidious factor that continues to drive the epidemic. Earlier this year, AFC launched a series of town hall meetings throughout Illinois to discuss what it would take for the state to get to zero new HIV transmissions in the next decade with residents across the state (an emerging project called Getting to Zero Illinois). The desperate need for more comprehensive sex ed in schools came up time after time.

Though the culture of shame is widespread and harmful, it is ultimately one we can control. When teachers, educational administrators and policymakers set about to change how sex ed is delivered, there are multiple paradigms they may choose to further the dialogue; the right decision is, and will always be, based on science.

Evidence-based programs like the Baltimore initiatives have demonstrated hard-won success rates proven over sustained periods of time. The kind of sex education that Meghan Williams and many others have advocated for recognizes gender diversity and other student concerns as valid and acceptable, and go beyond pregnancy prevention to give young people the tools they need to live their healthiest and happiest lives. Promising programs start early in a child’s educational trajectory, consistently deliver messaging about healthy relationships, and lay the groundwork for love and respect for one’s own body. In turn, these programs normalize the human drive for sex and create more functional gender dynamics throughout the lifespan.

SRAE, the alternate choice, is based on ineffective and detrimental solutions that promote abstinence-only and further archaic beliefs of gender stereotypes and discrimination against anyone outside of a narrow heterosexual paradigm.

Albert Einstein famously defined insanity as “repeating the same behaviors and expecting a different outcome.” In the U.S., funding for abstinence-only sex education programs began in the 1980s and has waxed and waned, notably having gained support during the George W. Bush administration. During this time and after years of being on the decline, teen pregnancy and STI infection rates actually increased.v So why on earth would we try this again?

Having learned from our mistakes, let’s support the most logical conclusion: that sex is a human need and that surrounding it with secrecy merely drives unhealthy behaviors underground and obscures solutions and resources for the people that desperately need them.

Let’s normalize sex in its many healthy forms and encourage our elected officials and schools to do the same for the benefit of our children’s futures.

There are lots of ways to get involved in supporting sex education in your school and community: these include contacting your local schools, finding out what the sex education laws look like in your state, and contacting your representatives and senators to tell them to end Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sexual Risk Avoidance programs. Visit Planned Parenthood’s site for more advocacy guidance.