In an elevator with strangers, Will Wilson regaled me with the story of recently losing his job as a tour bus guide when an insolent child called him a “fag.” Suffice it to say Wilson lost his temper in response. This somewhat disturbing story was humorous in its telling, though two men in the elevator shuffled their feet and cast sideways glances, apparently uncomfortable with such talk.

In an elevator with strangers, Will Wilson regaled me with the story of recently losing his job as a tour bus guide when an insolent child called him a “fag.” Suffice it to say Wilson lost his temper in response. This somewhat disturbing story was humorous in its telling, though two men in the elevator shuffled their feet and cast sideways glances, apparently uncomfortable with such talk.

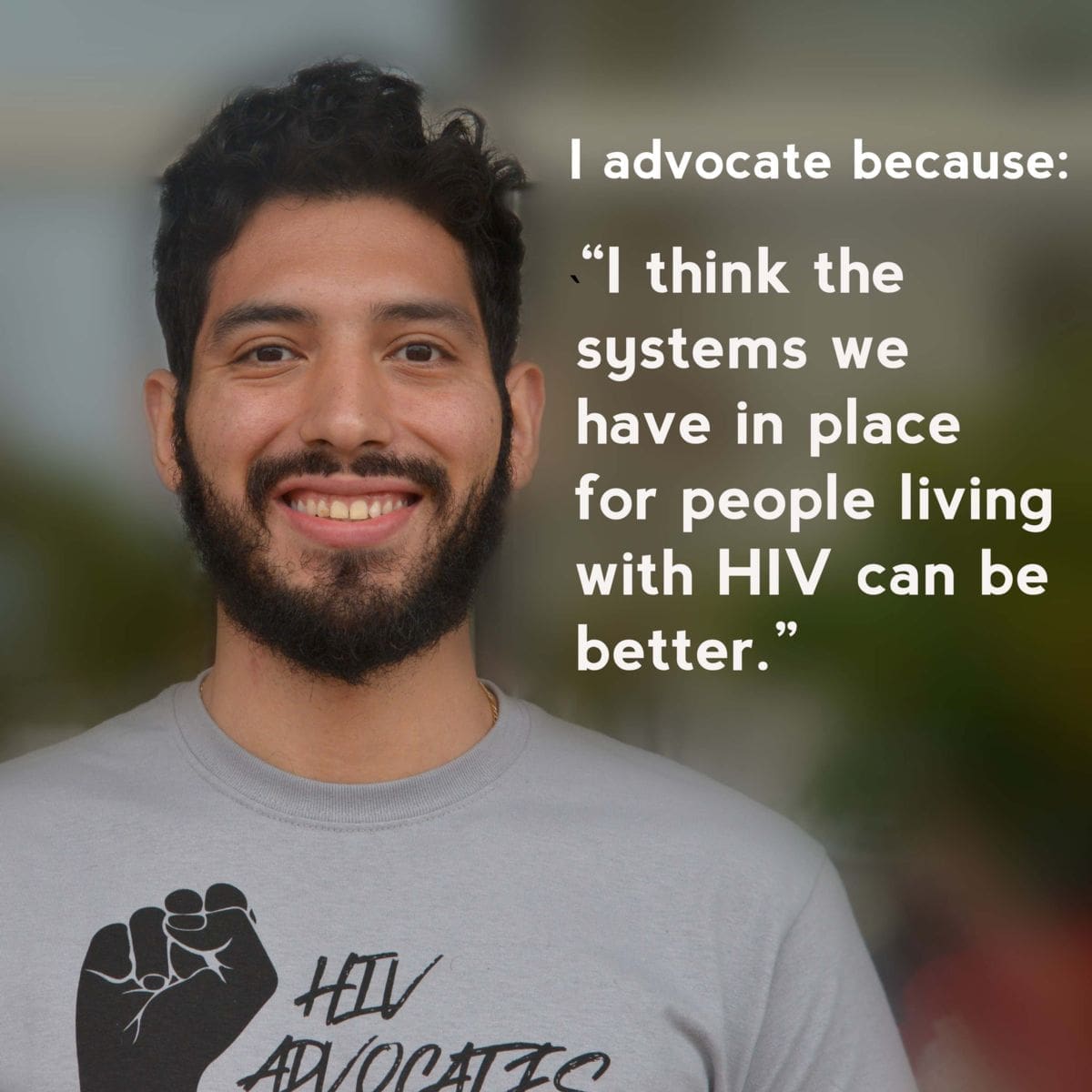

That anecdote is only to say that Will Wilson is an unabashedly honest, funny, fiery storyteller. He’s also a passionate AIDS activist with the Illinois Alliance for Sound AIDS Policy. Diagnosed with “full-blown AIDS” in 2002, Wilson (pictured at right) tells his story to beat down stigma and to advocate for affordable HIV/AIDS medicine for the many people who cannot afford to pay $3,000 a month to stay alive.

His pedigree as an advocate makes it all the more surprising that Wilson found himself nearly bumped from Illinois’ AIDS Drugs Assistance Program (ADAP) in early December. No stranger to the program, which provides assistance to low-income people with HIV/AIDS, Wilson found himself tangled up in the program changes implemented this year.

More than a month after filing his application, his drugs were at the pharmacy but off-limits to him, Wilson recalled in a recent interview over coffee. His application had not been approved.

“It’s like looking through a plate glass window and knowing you can’t reach what’s on the other side,” Wilson said “It’s just really, really, really scary.”

How did it happen?

This year, ADAP made some major program changes. For the first time ever, applicants must reapply for aid every six months — as opposed to every year. And the forms must be completed online instead of the old way of faxing forms in.

It turns out the reporting requirements are a bit more stringent this year, too. Wilson filed his application on Oct. 25. Four weeks later, having not heard anything about his application, he checked back in. Good thing he did — his application was marked as incomplete because he had not fully satisfied the program’s question about his source of income.

Since losing the tour bus guide job, his income was scant.

“The questions were really pretty invasive,” Wilson said. “It wasn’t good enough to say I’m not working … Where do you get your money from? So, I literally had to tell them I was begging.”

After a subsequent attempt, Wilson discovered his application was still considered incomplete. It took three more filing attempts and a call to State Rep. Sara Feigenholtz’s office before his application was finally approved. (Feigenholtz is the House Human Services Committee chair and oversees ADAP’s funding.)

It was a close call. Wilson received his medicine the day before he ran out.

What’s the moral of the story?

It’s not that ADAP is a bad program, Wilson said. Actually, ADAP is an “excellent program” working through some changes.

“They’re really, really pleasant about it. It’s the whole growing pains thing,” Wilson said. “Eventually, it’s going to work out where it’s much more efficient for everyone.”

Wilson’s not alone, said John Peller, vice president of policy for the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. Applicants all over the state have been having similar issues with the ADAP changes.

The takeaway, Wilson said, is that ADAP applicants need to be more proactive and thorough in their applications. If you don’t hear anything, it’s on you to call the ADAP office, Wilson said. Make sure you or your case manager are familiar with the program changes.

“That’s the takeaway, you have to be more complete than you think you do,” Wilson said. “Make sure your case manager knows to dot all the I’s and cross all the T’s. It’s your responsibility.”