By Brian Solem

Housing and health are inseparably linked. You’re more likely to be in consistently good health if your housing costs (rent or mortgage plus utilities, groceries and other household needs) take up a limited slice (30% by most estimates) of your overall budget. If you are barely making ends meet, your health might show it, and you become more susceptible to unstable housing or homelessness.

Overall health is impacted by more than just your ability to receive health care,” said Jessie Beebe, Director of Behavioral Health for the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “It’s all about the social determinants of health: environmental factors like a person’s living conditions, community, income, transportation options, education and more.”

A person’s economic situation can determine their physical and mental health — regardless of their race or ethnicity. A 2012 study in the International Journal of Health Services found that health disparities between people of different races were eclipsed by the disparities existing between high- and low-income groups within each racial/ethnic group. According to a Federal Reserve report on the economic wellbeing of U.S. households in 2016, 36% of respondents earning $40,000 or less went without some form of medical treatment. Only 23% of people with incomes between $40,000 and $100,000 and 9% of people making over $100,000 said the same thing. Housing isn’t the only reason someone might not get that cough or rash checked out, or refill their HIV meds before they run out, but it can have an impact.

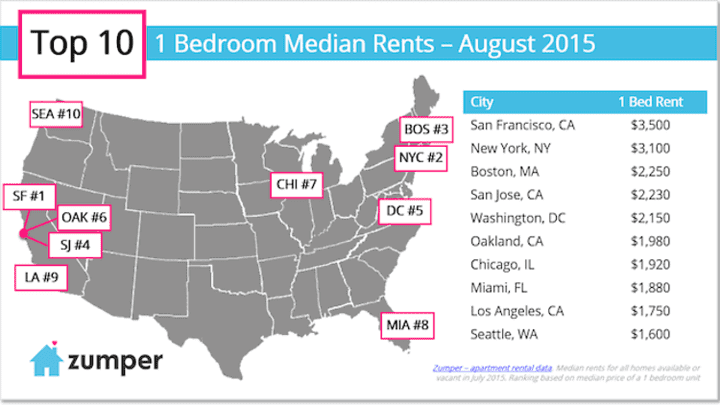

But what does income have to do with housing? Housing is the most fixed item in a person’s personal budget, which means it tends to get prioritized over all other recurring expenses that a person has to cover. Your rent and utility costs don’t typically change too much from month to month — but they do seem to be rising for most Americans, to the point that you need to make $21.21 per hour to rent a two-bedroom apartment (on average — this is much higher in big cities!). If your rent is significantly higher than you can “afford,” you’re not living with a cushion for health expenses.

Picture Rae — a fictional single mom with two children living in Chicago making just $10.75 per hour (the Chicago minimum wage) as a personal care aide. She’d have to work almost 80 hours a week to afford the average two-bedroom apartment in Illinois according to this study.

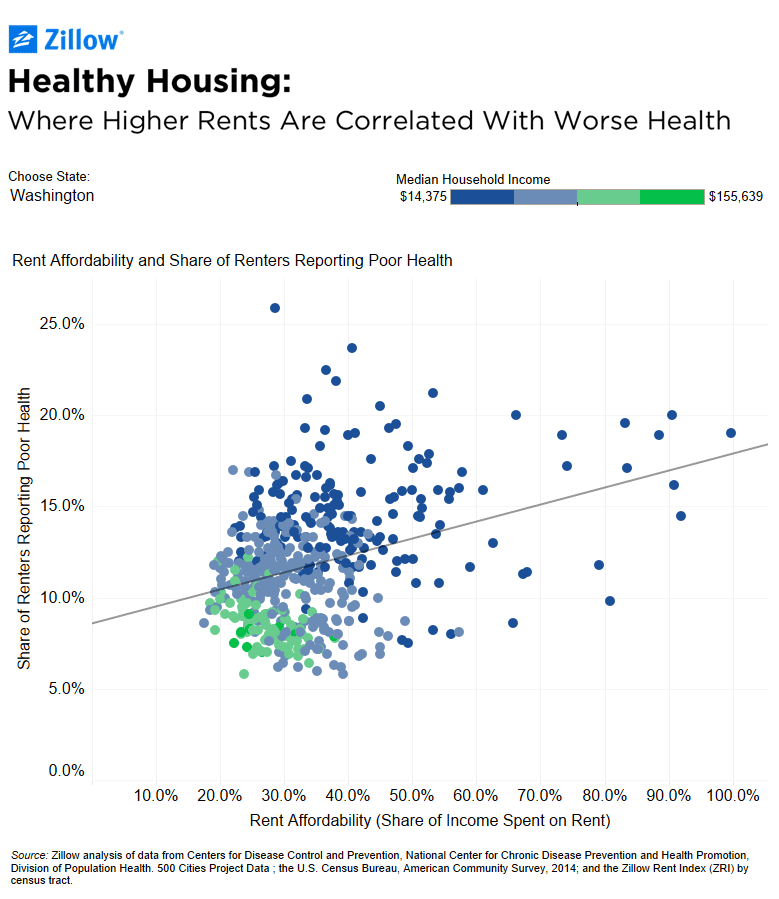

The message from our friends at Zillow is clear: if you can’t afford your rent, you’re very likely to also have poor health. If housing were more affordable, people could spend more on doctor visits, medicine and healthier food and lifestyle choices. But as long as housing costs continue to rise, people’s health will continue to decline. And if the Trump administration deprioritizes the needs of poor Americans and enact policies that actually increase housing costs, our health may experience a dramatic decline in 2018.

What’s the solution (besides burning capitalism to the ground and starting all over again)? Cities like New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco are making big moves to end homelessness and unstable housing by creating new homes for people who find themselves suddenly without housing. “Chicago just took a first step in the right direction by allocating $1.8 million in the calendar year 2018 city budget for a flexible rental subsidy pool targeted to homeless people with chronic illnesses.” Many people living at the edge of their budget who experience a sudden financial catastrophe like the loss of a job or a health crisis may find themselves without a home. Veronica, a real working mom from Chicago who needed emergency housing assistance from AFC to save her family from eviction after she and her husband became sick, is one such person.

“When you give a person a stable home, they can think about their health,” said Jessie. “They can have stability and safety that they didn’t have before, and then have space in their brain to worry about going to the doctor and taking good care of themselves.”

A home is reassurance. A home is strength and security. A home is a necessary ingredient in helping a person reach their full potential — in health and in life. Increasing wages, lowering housing costs and maintaining equitable approaches to providing health care for all (like the Affordable Care Act) can make a home possible for everyone.

Next steps:

What’s the real cost of living in your area? Find out using this Living Wage Calculator.

Sign up to take action with the National Low-Income Housing Coalition.

Learn more about social determinants of health through this interactive infographic.

Need a home or help keeping your home? Learn about housing programs offered by AFC and other organizations.